When clinicians talk about severe vision loss or total blindness, the discussion often stays at the clinical level. In this article, I deliberately take a different approach. I compare Diagnosys Espion and Roland RETIport not as brands, but as engineering systems designed to measure microvolt-level biological signals. The focus here is not on marketing features or automated interpretations, but on what these instruments actually do: how they acquire signals, where their technical limits lie, how reliably they behave over time, and why those details matter when negative or borderline results carry real clinical and legal weight. This is an engineering look at objective electrophysiology — written for clinicians and institutions that want to understand what they are really relying on.

Why Electrophysiology Still Matters in Objective Vision Assessment

I do not treat total blindness as a philosophical or purely clinical concept. From an engineering perspective, it is a boundary condition — the point at which a measurement system can no longer reliably detect a response above its own noise and uncertainty. Everything before that point is a matter of signal quality, system stability, and defined thresholds.

Many clinical tools used to assess vision rely on patient cooperation or interpretation. Electrophysiology is different. It converts retinal and cortical activity into electrical signals that can be measured, averaged, and compared against known limits. That alone explains why these systems remain relevant in pediatrics, neuro‑ophthalmology, medico‑legal cases, and advanced disease — not because they are new, but because they are measurable.

I consider this distinction important. Engineers tend to trust systems that expose their limits rather than hide them behind interpretation. Electrophysiology does exactly that.

What Is Actually Being Measured

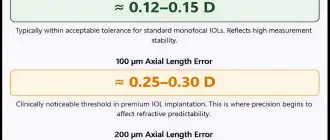

Electroretinography (ERG) and visual evoked potentials (VEP) measure bioelectrical signals generated by the visual system in response to controlled light stimuli. These signals are small by any engineering standard. Typical full‑field ERG responses are on the order of 50–300 µV. Pattern or flash VEP responses recorded at the scalp are often 1–10 µV and sometimes lower.

These amplitudes immediately define the problem. When signal magnitude approaches the microvolt range, the system becomes sensitive to electrode impedance, thermal noise, electromagnetic interference, and motion artifacts. In practice, what the clinician sees as “no response” usually means that repeated stimulation fails to produce a reproducible waveform exceeding the system’s noise floor under standardized conditions.

Engineers rarely think in absolutes. Absence of signal always means absence within a defined bandwidth, sensitivity, and averaging strategy. That mindset applies directly here.

From Biological Response to Instrument Output

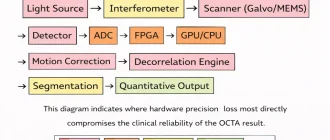

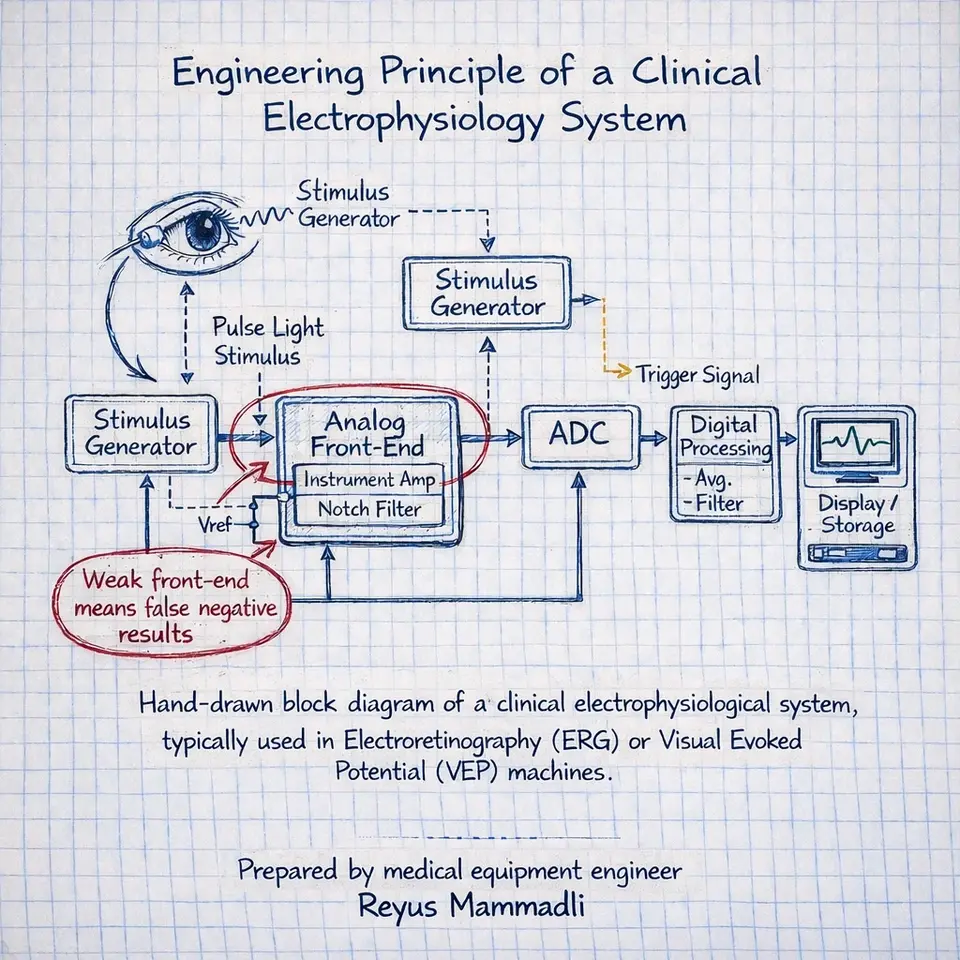

All clinical electrophysiology systems follow the same measurement chain: stimulus generation, signal acquisition, analog amplification, digitization, filtering, and averaging. Each block imposes constraints.

If the analog front‑end introduces input‑referred noise of even 0.2–0.3 µV RMS, detecting low‑amplitude cortical responses becomes statistically uncertain. If ADC resolution or timing stability is insufficient, averaging cannot recover what was never captured accurately. These are not theoretical issues; they determine whether residual function is detectable at all.

This is why I am cautious when interpreting negative findings. A system does not detect “blindness.” It fails to detect a signal above its own technical limits.

Why I Focus on These Two Systems

In this analysis I focus on two platforms: Diagnosys Espion and Roland Consult RETIport / RetiCom systems.

The reason is straightforward and technical. Both platforms provide unusually transparent documentation: acquisition parameters, amplifier characteristics, stimulation methods, electrode configurations, and standardized protocols. This allows an evaluation based on known system behavior rather than assumptions.

There are other electrophysiology devices on the market, including compact and highly automated systems. Some are effective within their intended scope. However, when internal signal processing, detection thresholds, or noise characteristics are not disclosed, meaningful engineering comparison becomes speculative. I consider it professionally inappropriate to compare systems I cannot technically inspect.

That does not rule out future analysis. It simply sets a boundary for what can be evaluated honestly today.

Clinical Scope Beyond Total Blindness

Neither of these systems is designed primarily to confirm total blindness. In routine practice they are used to characterize retinal dysfunction, differentiate retinal from post‑retinal pathology, monitor progression, and assess functional outcomes of therapy.

Total blindness appears only when responses fall below detectable limits across standardized protocols. In engineering terms, it is an endpoint of a wide dynamic range measurement system — not its primary objective.

Engineering Interpretation of “No Detectable Response”

Every measurement system has a noise floor. Averaging reduces random noise, but systematic artifacts remain. When repeated measurements under controlled conditions fail to produce a stable waveform above that floor, the system reports no detectable response.

Engineers are trained to phrase this carefully. It is not a declaration of absence, but a statement about detectability. Understanding that distinction is essential when electrophysiology contributes to conclusions about severe vision loss.

Engineering Boundaries of Objective Electrophysiology

This text deliberately avoids framing blindness as a binary clinical label. From an engineering standpoint, electrophysiology defines boundaries: signal amplitude relative to noise, reproducibility across trials, and stability under standardized conditions.

When responses fall below detectable limits across properly executed protocols, the system reports absence of measurable activity. That outcome is not philosophical and not speculative — it is bounded by amplifier noise, electrode behavior, stimulus stability, and acquisition parameters. Understanding those bounds is essential before any clinical conclusion is drawn.

This perspective is what guides the technical analysis throughout the article: not whether vision exists in an abstract sense, but whether it can be detected, characterized, and trusted within the physical limits of the instrumentation.

The Two Reference Systems: Engineering Overview

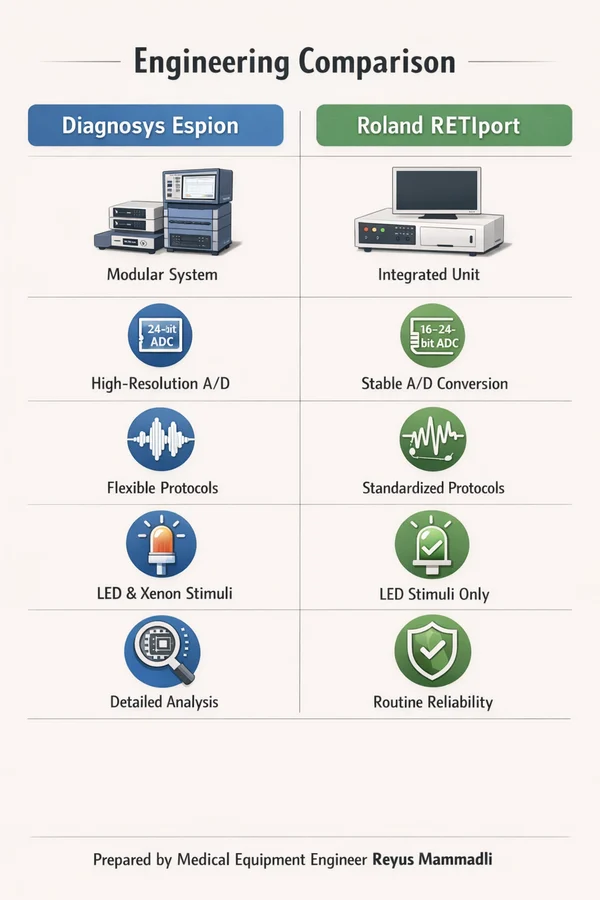

In this analysis, I work with two electrophysiology platforms that I consider technically inspectable and professionally fair to compare: Diagnosys Espion and Roland Consult RETIport / RetiCom. I deliberately limit the scope to these systems because their design philosophy and documentation allow me to evaluate real engineering decisions rather than speculate about hidden algorithms.

I want to be explicit here. Other electrophysiology systems exist and are actively used in clinics. Some of them are optimized for workflow, screening, or automation. However, when internal signal processing, detection thresholds, or hardware limits are not disclosed, I consider it inappropriate to draw engineering conclusions. What follows is therefore not a market survey, but a technically grounded comparison.

Diagnosys Espion — Engineering Profile

The Espion platform is built as a modular, research-grade clinical system. From an engineering perspective, its design clearly prioritizes signal integrity and configurability over simplicity. The architecture assumes that the user understands why parameters such as bandwidth, averaging count, and stimulus timing matter.

In my experience, systems like Espion are designed by engineers who expect the hardware to be pushed close to its physical limits. That usually means conservative analog design, generous headroom in the front-end, and minimal reliance on aggressive digital correction. This approach is common not only in medical electrophysiology, but also in EEG, EMG, and laboratory neurophysiology systems.

Roland Consult RETIport / RetiCom — Engineering Profile

Roland’s RETIport and RetiCom systems reflect a different, but equally valid engineering philosophy. The focus here is long-term reproducibility and standardized clinical behavior. The system feels deliberately conservative: fewer exposed parameters, strong adherence to established protocols, and emphasis on stability over flexibility.

From my engineering point of view, this is a design aimed at behaving predictably over many years. I have seen similar approaches in German industrial and medical instrumentation, where the priority is not peak performance on paper, but minimal drift and repeatable behavior across time and operators.

Side-by-Side Comparison: Core Engineering Characteristics

Table 1. System-Level Comparison

| Parameter | Diagnosys Espion | Roland RETIport |

|---|---|---|

| Design philosophy | Research-clinical hybrid | Conservative clinical |

| User control | Extensive parameter access | More standardized |

| Documentation depth | Very high | High |

This table already explains why these systems appeal to different users. One exposes more of the measurement chain, the other deliberately shields the operator from excessive tuning.

Analog Front-End Design: Practical Detectability Limits

Both systems rely on differential amplification with very high input impedance, typically exceeding 1 GΩ. This is essential when working with corneal and scalp electrodes whose impedance may vary between a few and several tens of kiloohms.

From available documentation and observed behavior, input-referred noise levels for clinical-grade electrophysiology systems are typically kept below approximately 0.2–0.3 µV RMS across the relevant bandwidth. In my experience, once noise rises above this range, low-amplitude VEP responses become unreliable regardless of averaging strategy.

The analog components used in such front-ends are commonly sourced from manufacturers like Analog Devices or Texas Instruments. These companies are widely used not only in medical devices, but also in industrial sensing, aerospace, and defense electronics. I tend to trust these components because I have seen them perform consistently in environments far less forgiving than a clinical lab.

Table 2. Analog Front-End Characteristics

| Parameter | Typical Value | Engineering Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Input impedance | >1 GΩ | Reduces electrode loading |

| Input noise | ≤0.3 µV RMS | Defines detection threshold |

| CMRR | >100 dB | Suppresses mains interference |

Digitization and Timing Architecture

After amplification, the signal is digitized using ADCs typically specified at 16 to 24 bits. Engineers know that the effective number of bits (ENOB) is always lower than the nominal resolution, but higher-resolution ADCs still provide valuable headroom for averaging and filtering.

Sampling rates in the range of 1–4 kHz are common. This range is sufficient to preserve ERG waveform morphology and VEP latency information without introducing unnecessary data volume. More importantly, clock stability at the parts-per-million level ensures that latency measurements remain comparable over time.

These digitization strategies are not unique to ophthalmic electrophysiology. Similar architectures are used in EEG systems and industrial vibration monitoring, where timing consistency matters more than raw bandwidth.

Table 3. Digitization Parameters

| Parameter | Typical Range | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| ADC resolution | 16–24 bit | Controls quantization noise |

| Sampling rate | 1–4 kHz | Preserves timing accuracy |

| Clock stability | ppm-level | Enables reproducible latency |

Stimulus Generation: Stability Over Novelty

Modern systems increasingly rely on high-power LEDs rather than xenon flash lamps. From an engineering standpoint, this shift is justified. LEDs offer better temporal control, longer service life, and simpler calibration, provided that thermal management is handled properly.

Timing jitter is a critical parameter. Even a few milliseconds of instability between stimulus onset and acquisition trigger can smear averaged responses and distort latency measurements. Well-designed systems maintain sub-millisecond synchronization, a requirement that mirrors practices in aerospace testing and high-speed industrial control.

Electrodes and Interfaces: The Unavoidable Constraint

No matter how well designed the electronics are, electrode behavior remains the least controllable part of the system. Contact impedance, movement, and biological variability all introduce uncertainty.

From my experience, engineers accept this limitation and design systems that detect and reject poor electrode conditions rather than attempting to compensate digitally. This conservative approach reduces false positives and increases trust in negative findings.

My Engineering Interpretation

Comparing these two systems, I do not see a competition of “better versus worse.” I see two different interpretations of the same physical constraints.

The Espion platform favors transparency and configurability, which I associate with research environments and complex diagnostic cases. The Roland systems favor predictability and long-term consistency, which aligns well with standardized clinical workflows.

What matters most to me as an engineer is that both systems operate well within known limits. When such systems report no detectable response, I consider that conclusion technically meaningful — not because blindness is absolute, but because the measurement chain is conservative, stable, and well understood.

Reliability as a Design Outcome, Not a Marketing Claim

In clinical electrophysiology, reliability is not an abstract quality. It is the cumulative result of hundreds of small engineering decisions: component derating, thermal margins, connector choice, firmware conservatism, and how aggressively the system is allowed to operate near its limits.

From my engineering perspective, the most trustworthy electrophysiology systems are not those that advertise the newest features, but those that demonstrate stable behavior across years of routine clinical use. In this field, a system that behaves identically today and five years from now is more valuable than one that produces marginally better performance under ideal conditions.

This matters directly when conclusions about severe vision loss or total blindness are involved. A negative result is only as credible as the long-term stability of the measurement chain that produced it.

Longevity of Hardware: What Actually Ages in These Systems

Electrophysiology systems age unevenly. The digital domain is usually not the limiting factor. CPUs, memory, and software platforms often remain functional far beyond their clinical relevance.

The components that age first are almost always:

- electrodes and electrode cables,

- connectors exposed to repeated mechanical stress,

- light sources and their calibration references,

- power supply components subjected to thermal cycling.

From my experience, clinics underestimate how much signal quality depends on these elements. A system with excellent electronics can gradually lose effective sensitivity simply due to aging cables or unstable optical output. Engineers are trained to think in terms of weakest links; here, those links are rarely glamorous.

Serviceability and Access to Critical Components

One of the most important but least discussed aspects of medical equipment procurement is serviceability. I advise clinicians and procurement teams to ask very direct questions about this.

From an engineering standpoint, the following details matter:

- Are analog front-end boards modular or monolithic?

- Can electrodes and stimulus components be replaced independently?

- Is calibration performed in software, hardware, or both?

Systems designed with modular subassemblies tend to survive longer in real clinical environments. When a failure occurs, replacing a known module is faster, cheaper, and less disruptive than shipping an entire system back to the manufacturer.

I have seen otherwise excellent systems become economically impractical simply because a single aging component was not designed to be serviceable.

Software Stability and Update Philosophy

Software is often presented as a selling point, but from an engineering perspective, stability matters more than novelty. In electrophysiology, a software update that changes signal processing behavior can silently alter longitudinal comparability.

Clinics should ask:

- How often are updates released?

- Do updates change signal processing or only user interface?

- Can previous software versions be retained for consistency?

In my judgment, conservative software policies are a strength, not a weakness. Systems that change slowly are easier to validate internally and easier to defend in clinical or legal contexts.

Technical Support: What Engineers Actually Rely On

Technical support quality directly affects system uptime and data quality. This is not limited to response time.

Important engineering-level questions include:

- Is support provided by application specialists or hardware-trained engineers?

- Are detailed service manuals available?

- Can raw data be accessed for troubleshooting?

In my experience, the most effective support teams are those that understand the measurement chain end-to-end. A support engineer who can discuss amplifier saturation or timing jitter is far more useful than one limited to scripted troubleshooting.

Questions I Recommend Asking Before Purchase

When evaluating electrophysiology systems for objective vision assessment, I recommend asking suppliers the following questions:

- What is the input-referred noise of the acquisition system under clinical conditions?

- How is stimulus timing verified and maintained over time?

- Which components are considered consumables, and what is their expected lifespan?

- What calibration procedures are required annually or after service?

- How is longitudinal consistency ensured across software updates?

These questions are rarely asked, but they directly affect long-term cost, reliability, and trust in negative findings.

Engineering Red Flags

Based on my experience, certain signs warrant caution:

- performance claims without quantified limits,

- heavy reliance on automated interpretation without access to raw data,

- inability to explain how noise and artifacts are handled,

- lack of clarity about service and calibration responsibilities.

None of these necessarily indicate a bad system, but they indicate areas where risk may be shifted from manufacturer to user.

Practical Guidance for Clinics

From an engineering standpoint, the most cost-effective systems over a ten-year horizon are those that:

- operate well within their physical limits,

- use mature, widely supported components,

- allow transparent inspection of signal quality,

- and are backed by technically competent support.

Clinics that prioritize these factors tend to experience fewer disruptions, lower total cost of ownership, and greater confidence in their diagnostic conclusions.

Final Engineering Perspective

Objective electrophysiology does not define blindness philosophically. It defines what can and cannot be detected within a conservative, well-characterized measurement system.

As an engineer, I place more trust in systems that acknowledge their limits than in those that promise to overcome them. When those limits are respected, the absence of a detectable response becomes a meaningful and defensible result.

For clinicians and institutions, understanding these engineering boundaries is not a technical luxury. It is a practical necessity that affects cost, reliability, and ultimately the quality of patient care.