From an engineering standpoint, intraocular pressure (IOP) is not a directly accessible variable. There is no implanted pressure transducer in routine clinical practice, and for obvious ethical and safety reasons, there will not be one. Every clinical tonometer therefore measures a mechanical response of the eye and converts it into pressure using a model. The accuracy of that conversion depends on how well the model matches the real mechanical behavior of the eye.

The eye is often intuitively compared to a fluid-filled sphere, but mechanically this analogy is weak. The cornea is a layered composite structure approximately 500–580 μm thick in untreated eyes, composed of epithelium, Bowman’s layer, stroma, Descemet’s membrane, and endothelium. More than 90% of its thickness is stroma, which exhibits viscoelastic behavior. Its response depends not only on load magnitude, but also on loading rate and history. This immediately implies that any measurement performed over milliseconds will differ from one performed over seconds, even at identical true IOP.

When a tonometer interacts with the cornea, several force components are involved simultaneously:

- intraocular pressure acting against deformation

- elastic resistance of the corneal tissue

- viscous damping of stromal collagen

- surface tension of the tear film

- friction or slip at the contact interface

No clinical device measures these components separately. They are lumped together into a single observable parameter.

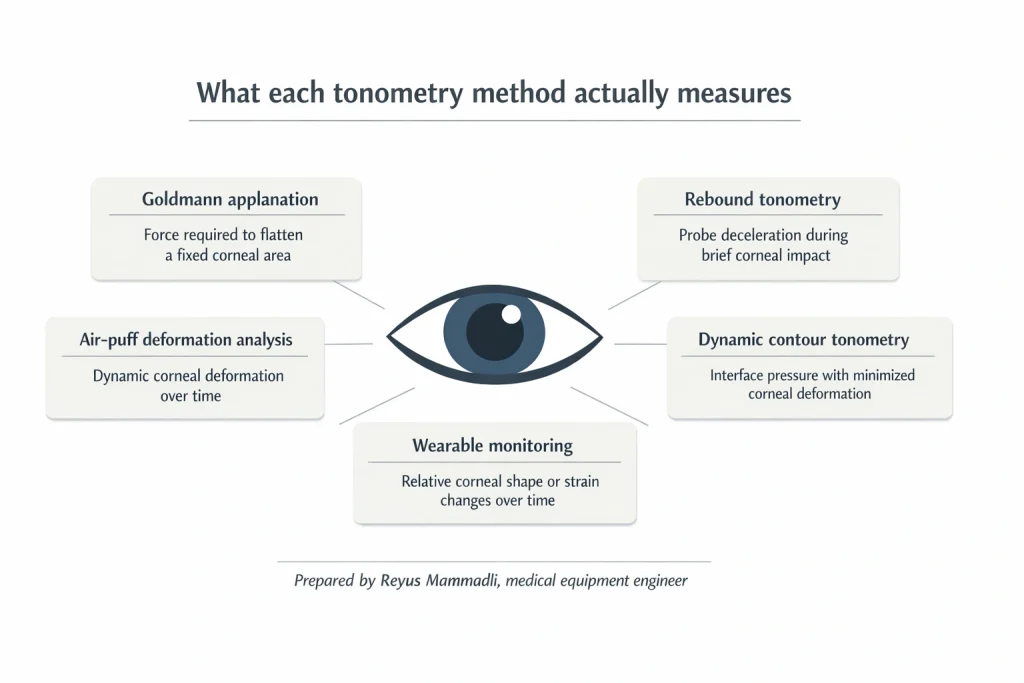

What Goldmann applanation actually measures

Goldmann applanation tonometry (GAT) estimates IOP by flattening a circular corneal area 3.06 mm in diameter. At this area, the applanation force is assumed to balance intraocular pressure over the flattened surface. The choice of 3.06 mm is not arbitrary: at this diameter, classical models suggest that corneal elastic resistance and tear film surface tension approximately cancel each other.

In real eyes, this cancellation is incomplete. Central corneal thickness (CCT) alone introduces measurable error. Empirical studies consistently show that a ±50 μm deviation from an assumed average corneal thickness (~520 μm) can shift measured IOP by approximately ±2–3 mmHg. This is not a calibration error of the device; it is a model mismatch. Thicker corneas resist applanation more strongly, thinner corneas less so.

In addition to thickness, corneal stiffness varies independently. Two corneas with identical thickness may differ significantly in biomechanical response due to collagen cross-linking, hydration, age, or surgical alteration. GAT cannot distinguish these factors. It integrates them into a single force reading.

From an engineering perspective, the strength of GAT lies elsewhere: repeatability. When performed correctly, under similar conditions, the method produces consistent results with intra-operator variability typically within ±1 mmHg. This is why it remains a reference. The method is stable, not because it is physically ideal, but because its errors are systematic and well-characterized.

Why newer clinical conditions stress the classical model

Several changes in modern ophthalmology directly challenge the assumptions behind applanation tonometry.

Refractive surgery is a primary example. Procedures such as LASIK and PRK alter stromal thickness and collagen structure. Postoperative corneas may be 80–150 μm thinner centrally and mechanically softer. In such eyes, GAT systematically underestimates IOP, often by 3–6 mmHg depending on ablation depth and individual biomechanics. Applying simple thickness-based correction factors does not fully resolve this, because stiffness and thickness are not linearly coupled.

Measurement dynamics also matter. GAT is a quasi-static method: the cornea is flattened over hundreds of milliseconds. Methods that interact with the cornea over 1–5 ms sample a different part of its viscoelastic response. This alone can produce differences of several mmHg between devices, even if both are functioning correctly.

Another limitation is operator dependency. Small variations in alignment, fluorescein amount, or applied force rate can shift readings by 1–2 mmHg. In busy clinical environments, this variability becomes non-negligible when trends over years are evaluated.

Engineering criteria that drive modern tonometry design

Modern tonometry systems are not attempts to find a single “true” IOP. They are attempts to control or redistribute error sources. From an engineering perspective, the main design goals are:

- Reduce sensitivity to corneal thickness and stiffness by changing the measurement principle

- Shorten interaction time to reduce viscous effects, or explicitly measure them

- Lower operator influence through automation and fixed geometry

- Improve repeatability across devices and users rather than absolute agreement with GAT

These goals are mutually conflicting. Reducing corneal influence often requires more complex sensors or dynamic measurement, which increases system complexity and cost. Improving ease of use may sacrifice some physical transparency of the measurement.

As a result, modern IOP measurement should be understood as a collection of engineered compromises. Each method deliberately emphasizes one aspect of the problem while accepting limitations elsewhere. Evaluating these methods requires looking at what physical quantity is actually measured, over what time scale, and how that quantity is translated into pressure.

This framework is essential before discussing individual modern technologies. Without it, differences between devices appear as inconsistencies. With it, they become predictable consequences of different engineering choices.

How modern tonometry technologies redistribute measurement error

Once the indirect nature of intraocular pressure (IOP) measurement is accepted, modern tonometry becomes easier to understand. Newer systems do not remove modeling error; they relocate it. Each technology changes how the cornea is loaded, over what time scale, and which mechanical properties dominate the response. From an engineering standpoint, this is deliberate error management, not incremental gadgetry.

Here I want to draw attention to the fact that > When different devices disagree by several mmHg, this is usually not a calibration failure. It is a consequence of measuring different physical proxies under different loading conditions.

Below, current approaches are described as physical measurement strategies rather than product categories.

Rebound-based measurement: millisecond interaction and inertial dominance

Rebound tonometry uses a very short mechanical impulse. A lightweight probe—typically a few milligrams—is accelerated toward the cornea and allowed to decelerate upon contact. The system records probe deceleration, rebound velocity, and contact duration, which are mapped to an estimated IOP.

Typical corneal contact times are 1–5 ms. At this time scale, stromal viscosity contributes less to the response than in slower methods. The cornea behaves closer to an elastic body with an inertial component, rather than a fully viscoelastic structure.

Dominant sensitivities shift accordingly:

- tear film surface tension becomes negligible

- operator-applied force is effectively eliminated

- intrinsic corneal stiffness becomes a primary confounder

In practice, rebound tonometry correlates reasonably with applanation methods between roughly 10 and 25 mmHg. Outside this range, systematic deviations appear. At higher IOP levels, underestimation is common because corneal deformation amplitude becomes small relative to probe dynamics.

Typical short-term repeatability is about ±1–1.5 mmHg under controlled conditions. Inter-method agreement with applanation tonometry is usually within ±3 mmHg.

Here it is important to note that > The probe itself is mechanically trivial but must be extremely consistent. Most manufacturers rely on simple stainless-steel or tungsten tips with tight mass tolerances, similar to components used in industrial contact sensors. Long-term reliability is high; drift usually comes from signal processing assumptions, not from the probe.

The engineering strength of rebound systems lies in automation and portability. Their weakness is the lack of explicit biomechanical measurement. Stiff and soft corneas with identical IOP may still produce different readings.

Dynamic contour measurement: reducing deformation instead of correcting it

Dynamic contour tonometry follows a different philosophy. A contoured tip approximating corneal curvature is placed against the eye. A miniature pressure sensor embedded in the tip measures interface pressure continuously over several seconds.

The assumption is that minimizing corneal deformation reduces biomechanical bias, allowing measured pressure to approach true IOP. While complete unloading is impossible, deformation is smaller than in applanation-based methods.

This approach introduces distinct technical constraints:

- stable mechanical coupling must be maintained for multiple cardiac cycles

- motion artifacts directly affect signal quality

- pressure sensors must exhibit low thermal drift

Most systems sample pressure at tens to hundreds of Hz, allowing extraction of mean IOP and ocular pulse amplitude.

Here it is important to note that > These systems typically use MEMS piezoresistive pressure sensors similar to those used in industrial and automotive pressure monitoring. The technology is mature and reliable, but it demands regular calibration. In my experience, neglected recalibration is a more common failure mode than sensor degradation.

Clinically, dynamic contour measurements show reduced dependence on corneal thickness, particularly in post-refractive surgery eyes. Systematic offsets of 2–4 mmHg relative to Goldmann readings are common and expected.

From an engineering view, dynamic contour tonometry trades operational simplicity for physical transparency. It reduces one class of error while increasing sensitivity to alignment and coupling quality.

Air-pulse deformation analysis: measuring corneal behavior explicitly

Air-puff–based systems combined with high-speed optical detection attempt to measure corneal biomechanics directly. A controlled air pulse deforms the cornea inward and allows it to recover. Optical systems track this motion at several thousand frames per second.

Two applanation events are typically identified: one during inward deformation and one during outward recovery. The difference between these events reflects viscoelastic energy loss within the cornea, often expressed as corneal hysteresis.

Outputs usually include:

- a Goldmann-correlated IOP estimate

- a biomechanically compensated IOP estimate

- independent biomechanical parameters

Here I want to draw attention to the fact that > High-speed imaging here is not exotic. Similar CMOS sensors and optical setups are widely used in industrial inspection and vibration analysis. The challenge is not the hardware, but the biomechanical model used to interpret the motion.

Repeatability is generally good, but agreement between different air-puff systems remains limited. Each manufacturer uses its own corneal model, and no single viscoelastic description has become standard.

These systems add information rather than certainty. They are valuable when corneal biomechanics are clinically relevant, but they increase interpretive complexity.

Continuous and semi-continuous monitoring: prioritizing dynamics over absolutes

Wearable and semi-continuous monitoring systems redefine the tonometry problem. Instead of estimating absolute IOP, they track relative changes over extended periods.

Most designs rely on sensorized contact lenses that detect changes in corneal curvature or strain. These signals correlate with IOP variation but are not direct pressure measurements. Sampling may continue for many hours, including nocturnal periods.

Key engineering limitations include:

- weak absolute calibration

- sensitivity to blinking, eyelid pressure, and lens positioning

- complex signal normalization

Here I want to draw attention to the fact that > These systems behave more like trend sensors than pressure gauges. Treating their output as mmHg is technically incorrect and leads to false expectations.

Despite these constraints, continuous monitoring captures phenomena that clinic measurements miss: nocturnal elevation, transient spikes, and variability patterns.

Comparative overview of engineering trade-offs

| Measurement strategy | Interaction time | Dominant sensitivity | Primary advantage | Key limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Applanation | Hundreds of ms | Thickness, tear film | Long-term reference | Biomechanical bias |

| Rebound | 1–5 ms | Stiffness, inertia | Automation, portability | High-IOP underestimation |

| Dynamic contour | Seconds | Alignment, coupling | Reduced deformation | Mechanical complexity |

| Air-puff biomechanical | Tens of ms | Modeling assumptions | Biomechanical insight | Interpretive burden |

| Wearable monitoring | Hours | External influences | Temporal dynamics | No absolute IOP |

Each modern tonometry method represents a conscious engineering compromise. None is universally superior. Their value becomes clear only when the physical assumptions behind each measurement are understood and respected.

At this point, it should be clear that modern tonometry does not offer a single definitive answer to the question “what is the intraocular pressure.” Instead, it offers multiple technically valid answers to slightly different questions. The practical challenge for clinicians is not choosing the most advanced device, but understanding what kind of measurement a given system actually produces.

Here I want to draw attention to a recurring misunderstanding: disagreement between devices is often interpreted as error. From an engineering perspective, disagreement is frequently expected. If two instruments excite the cornea differently, over different time scales, and rely on different mechanical models, numerical agreement is not a reasonable baseline expectation.

What modern measurements are actually good at

Each class of tonometry has a domain where it performs reliably. Outside that domain, uncertainty grows in predictable ways.

Applanation-based measurements remain strong where long-term comparability is required. Decades of clinical data are anchored to these values. Their weakness is not instability, but structural bias in eyes that deviate from the assumed corneal model.

Rebound methods excel in repeatability and usability. Their short interaction time reduces operator influence and allows frequent measurements. Here it is important to note that their strength is consistency, not universality. When used longitudinally with the same device, trends are often more reliable than absolute values.

Contour-based systems reduce dependence on corneal thickness and are particularly informative in post-refractive surgery eyes. The price paid is operational sensitivity. Small deviations in alignment or contact quality can outweigh theoretical advantages.

Air-puff systems with biomechanical analysis provide information that other methods simply do not. They answer a different question: how does this cornea behave under load? I want to emphasize that this is not an academic detail. In some patients, biomechanical parameters are more informative than a single pressure number.

Continuous monitoring systems abandon the idea of absolute pressure entirely. They are pattern detectors rather than gauges. Here I want to stress that treating their output as millimeters of mercury is a category error. Their value lies in temporal structure, not calibration.

How an engineer would choose a measurement strategy

From an engineering standpoint, choosing a tonometry method is an optimization problem with constraints. There is no global optimum.

The following questions are more useful than asking which device is “most accurate”:

- Is this a single measurement or a long-term trend?

- Has the cornea been surgically altered?

- Will measurements be performed by the same operator and device over time?

- Is variability or peak detection more clinically relevant than absolute value?

Here I want to point out something that is rarely stated explicitly: mixing methods without understanding their biases is worse than sticking to an imperfect but consistent one. Engineers accept systematic error if it is stable. Clinicians often do the same, sometimes without realizing it.

What patients should realistically be told

Patients increasingly notice that pressure values change between visits or between clinics. This is often interpreted as poor measurement quality. From an engineering perspective, it is a predictable outcome of using different measurement models.

I want to underline that explaining this honestly builds trust rather than confusion. Patients do not need simplified promises; they need coherent explanations. Saying that different devices “measure the eye in different ways” is technically accurate and usually sufficient.

It is also important to explain that pressure fluctuates naturally. Diurnal variation of several mmHg is normal. Single measurements are snapshots, not averages. Continuous monitoring has shown that some patients experience pressure peaks outside clinic hours that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Reliability, maintenance, and long-term behavior

From the inside of the device, reliability is rarely about catastrophic failure. It is about drift, calibration, and gradual loss of alignment. Sensors used in tonometry are generally mature technologies borrowed from industrial and automotive applications. Their intrinsic failure rates are low.

Here I want to draw attention to a less discussed issue: procedural drift. Changes in staff, workflow, or maintenance discipline often affect measurement consistency more than sensor aging. Engineering robustness cannot fully compensate for operational variability.

Where the field is actually going

Modern tonometry is not converging toward a single superior method. It is diverging into complementary tools. This is a sign of maturity rather than fragmentation.

Future systems will likely combine:

- point measurements with biomechanical context

- clinic-based accuracy with out-of-clinic dynamics

- stable hardware with increasingly sophisticated software interpretation

I want to stress that this is an evolutionary process. The underlying physics of the eye has not changed. What has changed is our willingness to accept complexity instead of hiding it behind a single number.

Final engineering perspective

Intraocular pressure is not a value waiting to be measured. It is a parameter inferred through models, assumptions, and compromises. Modern technologies do not remove these compromises; they make them explicit.

For clinicians, the most important skill is not selecting the newest device, but understanding what question each measurement answers. For patients, the most important message is that variability does not imply unreliability.

From an engineering point of view, this is progress. Not because uncertainty disappeared, but because it is now better understood and better managed.

References

- International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

https://www.iso.org - IEEE – Engineering and Biomedical Publications

https://www.ieee.org - ASME – Journal of Biomechanical Engineering

https://www.asme.org - SPIE – Optical and Imaging Engineering

https://www.spie.org - NIST – Measurement Science and Sensor Calibration

https://www.nist.gov - Elsevier – Engineering and Measurement Systems Literature

https://www.elsevier.com - Wikipedia – Technical Reference (Instrumentation and Sensors)

https://en.wikipedia.org