Ophthalmic Nd:YAG Lasers as a Clinical Platform

I approach ophthalmic Nd:YAG laser systems as a mature but still actively engineered class of equipment. They are often described narrowly through a single clinical indication, yet from an engineering standpoint they are modular laser platforms optimized for precise photodisruption in a confined optical volume. Clinics do not purchase a “procedure”; they purchase a system architecture built around a pulsed solid‑state laser, precision optics, real‑time aiming, and safety‑critical control electronics. My goal here is to explain how these systems are built, why the underlying technology remains relevant, and which design decisions matter when a clinic selects a modern platform.

Nd:YAG ophthalmic lasers operate at a wavelength of 1064 nm, typically delivering Q‑switched pulses in the 2–10 ns range with pulse energies adjustable from 0.5 to 10 mJ at the focal plane. These numbers are not arbitrary. They are tightly linked to plasma formation thresholds in transparent ocular media and to the mechanical shockwave needed to separate tissue without thermal spread. From an engineering perspective, this combination of wavelength, pulse duration, and peak power remains difficult to replicate with alternative laser types at comparable cost and reliability.

The infographic below summarizes the key engineering and ownership factors discussed in detail throughout this article.

Why Nd:YAG Remains a Relevant Platform

The continued dominance of Nd:YAG in ophthalmology is not inertia; it is the result of stable physics and predictable engineering behavior.

At 1064 nm, absorption in corneal and lenticular tissue is low, which means energy deposition is dominated by optical breakdown at the focal point rather than bulk heating. With a 5 ns pulse at 4 mJ, peak power exceeds 0.8 MW, sufficient to generate a plasma spark within a focal volume on the order of 10–20 µm. This regime is extremely forgiving in terms of optical alignment tolerances compared to femtosecond systems, yet still precise enough for intraocular use.

From my experience evaluating these systems, this predictability is a major reason clinics continue to invest in Nd:YAG platforms rather than replacing them with more complex ultrafast lasers. The engineering trade‑off favors robustness and repeatability over ultimate spatial resolution.

Engineering Perspective: Stability Over Novelty

I consider Nd:YAG a “solved” laser medium in the best possible sense. Neodymium‑doped yttrium aluminum garnet crystals have been mass‑produced for decades, with crystal growth processes stabilized in Japan, Germany, and the United States. Typical rod lifetimes in ophthalmic duty cycles exceed 50–100 million pulses, which for many clinics corresponds to 10–15 years of operation before output degradation becomes noticeable.

This long‑term stability is not glamorous, but it directly translates into predictable ownership costs and minimal calibration drift. For procurement teams, that matters more than incremental performance gains.

Core System Architecture of Modern Ophthalmic Nd:YAG Lasers

Modern ophthalmic Nd:YAG systems share a common architecture, even across different manufacturers. Understanding this architecture helps separate meaningful engineering differences from cosmetic ones.

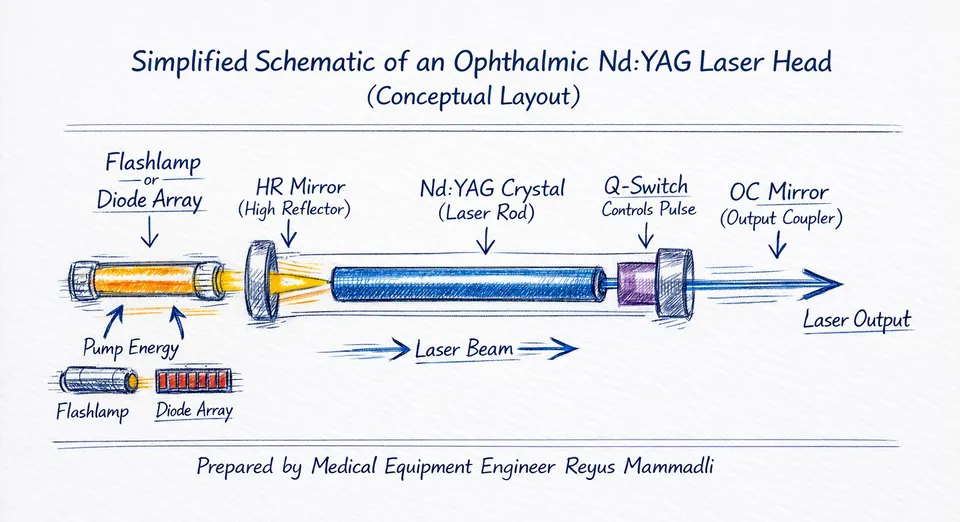

Laser Generation Module

The laser head typically consists of:

- A Nd:YAG crystal rod, 3–6 mm in diameter and 50–80 mm in length

- A xenon flashlamp or, in newer designs, laser diode pumping

- High‑reflectivity dielectric mirrors optimized for 1064 nm

Most systems still rely on flashlamp pumping because of its simplicity and high peak power capability. Flashlamps are usually sourced from suppliers in Germany or the United States and are rated for 10–20 million flashes. In real clinical use, I often see replacement intervals closer to 5–8 million pulses, especially in high‑volume centers.

Diode‑pumped designs exist and offer better electrical efficiency and higher upfront cost. From a beam‑quality standpoint, diode pumping also enables a more stable TEM₀₀ mode profile, which becomes particularly relevant at low pulse energies (≈0.8–2 mJ), where plasma formation margins are narrow. In my view, this improved spatial mode can translate into more predictable breakdown thresholds, but only if thermal management and cavity alignment are well controlled. In my view, diode pumping makes sense primarily for compact or portable platforms, not necessarily for fixed slit‑lamp‑based systems.

Q‑Switching and Pulse Control

Pulse formation is governed by an electro‑optic or acousto‑optic Q‑switch. Most ophthalmic systems use KD*P or RTP Pockels cells, driven at voltages between 2 and 4 kV. The timing jitter of the Q‑switch driver directly affects pulse energy consistency.

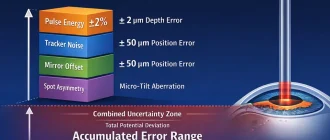

Modern controllers achieve pulse‑to‑pulse energy stability within ±5%, which is a meaningful improvement over older systems that often drifted beyond ±10% as components aged. I consider this stability a critical parameter, especially when clinicians rely on minimal incremental energy increases during procedures.

Optical Delivery and Focusing

The optical path includes beam expansion, collimation, and final focusing through a high‑numerical‑aperture objective integrated into a slit‑lamp microscope. A critical but often underexplained feature is posterior/anterior focus offset, where the focal point of the therapeutic beam is deliberately shifted relative to the visible aiming beam. From an engineering standpoint, this is usually implemented via controlled axial movement of a lens group within the collimator or focusing assembly, typically on the order of 50–500 µm depending on application. Typical focal lengths range from 100 to 160 mm, producing spot sizes near 10 µm at focus.

High‑quality systems use multi‑element glass optics manufactured in Japan or Germany, with anti‑reflection coatings optimized for both 1064 nm (treatment beam) and 635–650 nm (aiming beam). These same optical suppliers often serve aerospace and defense industries, which is not incidental; coating durability and angular stability are directly inherited from those fields.

From an engineering standpoint, optical alignment stability over time is more important than absolute spot size. I have seen systems with theoretically excellent optics underperform simply due to mechanical drift in the slit‑lamp interface.

Integrated Slit‑Lamp Design as a Platform Choice

Nearly all ophthalmic Nd:YAG lasers are integrated with a slit‑lamp biomicroscope. This is not merely a convenience feature; it is a core design decision.

The slit‑lamp provides:

- Coaxial visualization of the focal volume

- Mechanical stability within tens of micrometers

- Familiar ergonomics for ophthalmologists

Modern platforms typically use LED‑based illumination sources rated for 20,000–30,000 hours, replacing older halogen lamps. This reduces heat load and eliminates one of the more frequent maintenance points in legacy systems.

Engineering Opinion: Mechanical Interfaces Are the Hidden Risk

In my assessment, the weakest point in many Nd:YAG platforms is not the laser but the mechanical coupling between the laser head and the slit‑lamp frame. Bearings, adjustment screws, and vibration isolation elements are often sourced from general industrial suppliers rather than precision optical manufacturers.

I routinely advise clinics to inspect:

- Repeatability of focus after repositioning

- Mechanical backlash in joystick controls

- Long‑term rigidity of mounting brackets

These factors rarely appear in specification sheets, yet they directly affect real‑world precision.

Control Electronics and User Interface

Modern systems rely on embedded controllers, typically ARM‑based microcontrollers or industrial SBCs sourced from the US or Taiwan. These controllers manage:

- Energy selection in 0.1–0.2 mJ increments

- Pulse repetition rates up to 2–3 Hz

- Safety interlocks and fault detection

Software is usually proprietary but built on standard real‑time operating systems. I often see components and design philosophies borrowed from industrial laser marking and materials‑processing systems, which is a positive sign. Those industries demand uptime and repeatability comparable to clinical environments.

From an engineering perspective, I value conservative software design over flashy graphical interfaces. Systems that log pulse counts, flashlamp hours, and fault histories provide tangible long‑term value during servicing and resale.

Early Selection Criteria Clinics Often Overlook

Before comparing brands or models, clinics should evaluate a few baseline engineering parameters:

| Parameter | Typical Modern Value | Why It Matters |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse duration | 2–6 ns | Determines plasma efficiency |

| Energy stability | ±5% | Affects predictability |

| Optical alignment drift | <20 µm/year | Impacts long‑term accuracy |

I believe these parameters are more informative than headline maximum energy figures. A system capable of 10 mJ is not inherently better than one capped at 7 mJ if stability and alignment are superior.

At this point, it becomes clear that ophthalmic Nd:YAG lasers should be evaluated as engineered platforms rather than single‑purpose tools. In the next stage of analysis, the differences between contemporary systems begin to matter far more than the shared fundamentals.

Engineering Differences Between Contemporary Ophthalmic Nd:YAG Laser Systems

Once the fundamental architecture of ophthalmic Nd:YAG lasers is understood, the real differentiation begins. Modern systems sold in the United States are no longer distinguished by wavelength or basic pulse physics; those parameters are effectively standardized. Instead, engineering value emerges in how consistently a system delivers energy, how precisely it maintains optical alignment, and how serviceable it remains over years of clinical use.

From an engineering and procurement standpoint, this is where specifications stop being academic and start translating into operational reality.

Energy Generation and Pulse Consistency in Modern Systems

Most contemporary ophthalmic Nd:YAG platforms offer a nominal pulse energy range from 0.3–0.5 mJ up to 8–10 mJ, adjustable in 0.1–0.2 mJ steps. What matters more than the upper limit is how reliably the system delivers energy at the lower end of that range.

In practice, I evaluate pulse consistency by looking at three parameters:

- short‑term pulse‑to‑pulse stability,

- drift over a typical treatment session (10–20 minutes),

- long‑term drift as flashlamps or pump diodes age.

Modern systems typically specify ±5% energy stability, but real‑world measurements often reveal differences between platforms using similar headline numbers.

| Aspect | Well‑Engineered Systems | Marginal Systems |

|---|---|---|

| Pulse stability (short term) | ±3–5% | ±8–12% |

| Energy drift over session | <3% | 5–10% |

| Compensation algorithms | Active feedback | Open‑loop |

In my experience, systems with closed‑loop energy monitoring—using internal photodiodes sampling a fraction of each pulse—maintain usable low‑energy performance far longer into the life of the laser head. This is a meaningful engineering distinction, not a cosmetic one.

Flashlamp vs Diode Pumping: Practical Differences in 2020s Platforms

While flashlamp‑pumped Nd:YAG lasers remain dominant, diode‑pumped solid‑state (DPSS) designs are increasingly present in premium systems.

Flashlamp‑Pumped Designs

Flashlamp systems remain attractive due to:

- lower initial cost,

- simpler high‑voltage electronics,

- tolerance to optical misalignment.

Typical flashlamps operate at 300–800 V with pulse currents exceeding 100 A, generating significant thermal and mechanical stress. Rated lifetimes are often quoted as 10–20 million pulses, but in high‑volume clinics I routinely see lamp replacement intervals closer to 5–7 million pulses.

From an engineering perspective, flashlamps are forgiving but consumable. Their degradation curve is gradual, which allows clinics to plan maintenance predictably.

Diode‑Pumped (DPSS) Designs

DPSS systems use laser diode arrays—often manufactured in Japan or the United States—to pump the Nd:YAG crystal directly. These diodes typically operate at 808 nm, with electrical‑to‑optical efficiencies exceeding 40–50%, compared to <5% for flashlamps.

The key technical advantage is beam quality. DPSS cavities more consistently support TEM₀₀ operation, which improves plasma formation reliability at energies below 2 mJ. I see this as particularly relevant for clinicians who prefer minimal incremental energy steps.

However, diode lifetimes, while often quoted as 20,000–30,000 hours, are highly sensitive to thermal management. Poor heat sinking or fan degradation can shorten usable life dramatically. This makes DPSS designs more sensitive to maintenance discipline.

Optical Train Quality and Long‑Term Alignment

Across modern systems, optical design quality varies more than many buyers expect. Differences emerge in:

- lens material and coating durability,

- mechanical mounting tolerances,

- thermal expansion compensation.

High‑end platforms typically use multi‑element glass optics sourced from Japanese or German manufacturers, with coating durability tested to >10⁸ pulses at 1064 nm. Lower‑cost systems may meet initial performance targets but show alignment drift after repeated thermal cycling.

| Optical Feature | Robust Design | Cost‑Optimized Design |

|---|---|---|

| Coating lifetime | >100 million pulses | <30 million pulses |

| Alignment drift | <20 µm/year | 50–100 µm/year |

| Mechanical mounts | Precision machined | Cast or stamped |

From my standpoint, alignment drift is one of the most underestimated long‑term performance degraders. A system can remain “within spec” while still becoming less predictable for the operator.

Focus Offset Mechanisms and Mechanical Reliability

Posterior/anterior focus offset is now standard across most modern Nd:YAG platforms. Technically, this is achieved by shifting a lens group within the collimator or focusing assembly, typically over a range of ±50 to ±500 µm.

The engineering question is not whether the feature exists, but how it is implemented:

- manual cam mechanisms,

- stepper‑motor‑driven stages,

- voice‑coil or piezo‑assisted micro‑positioners.

In systems where offset adjustment relies on fine mechanical cams and set screws, wear and backlash tend to appear after 3–5 years of use. Motorized implementations improve repeatability but introduce additional control electronics and failure points.

My engineering preference is for mechanically simple but over‑dimensioned designs. Precision is useless if it degrades faster than the laser source itself.

Control Software and Human–Machine Interface

Modern ophthalmic Nd:YAG systems typically run on embedded controllers using ARM‑based processors and real‑time operating systems. Energy selection resolution of 0.1 mJ is common, but the underlying control logic differs significantly between manufacturers.

Some platforms implement:

- software‑based energy ramping limits,

- pulse history logging,

- component life counters tied to service alerts.

Others rely on minimal firmware with little transparency to the user or service engineer.

I consistently view comprehensive logging as an engineering advantage. Systems that record pulse counts, energy levels, and fault events allow clinics to make data‑driven maintenance decisions rather than reactive ones.

Serviceability as an Engineering Differentiator

From a procurement perspective, serviceability often outweighs marginal performance gains.

| Service Aspect | Engineering‑Focused Design | Cost‑Driven Design |

|---|---|---|

| Access to laser head | Modular | Fully integrated |

| Consumable tracking | Software‑assisted | Manual |

| Calibration procedure | Guided, repeatable | Technician‑dependent |

I have seen technically excellent systems become operational liabilities simply because replacing a flashlamp or recalibrating energy output required excessive downtime.

At this stage, differences between contemporary Nd:YAG systems are no longer subtle. They are embedded in energy control strategies, mechanical design choices, and software transparency. These factors define whether a platform ages gracefully or becomes unpredictable long before its nominal end of life.

Contemporary Ophthalmic Nd:YAG Systems in Active U.S. Clinical Use

To move from abstract engineering discussion to practical system selection, it is necessary to look at specific platforms that are currently sold and used in the United States. Below, I focus only on systems for which publicly available technical documentation, user manuals, or regulatory summaries exist. Where manufacturers do not disclose details, I state that explicitly.

Lumenis Ultra Q Reflex

The Ultra Q Reflex remains one of the most widely installed Nd:YAG platforms in U.S. clinics. It is a flashlamp‑pumped system integrated with a slit‑lamp and marketed as a high‑throughput, general‑purpose platform.

From available documentation, the system offers pulse energies up to approximately 8–10 mJ with adjustable steps down to ~0.5 mJ, and pulse durations in the low‑nanosecond range typical for Q‑switched Nd:YAG systems.

Engineering observations:

- The flashlamp design is conservative and well understood, favoring predictable degradation over time rather than abrupt failure. From an engineering standpoint, this means output power decays gradually as electrode erosion increases, giving clinics clear warning signs rather than sudden loss of functionality. I generally consider this behavior preferable in high‑volume environments.

- The optical train is robust, but alignment stability relies heavily on mechanical rigidity of the slit‑lamp assembly. In this platform, optical precision is achieved more through mechanical stiffness than active compensation, which works well as long as mechanical wear is controlled.

- Posterior/anterior offset is implemented mechanically. This choice minimizes electronic complexity, but it also means that cams, screws, or sliders are subject to wear. In my experience, this is not a critical flaw, but it does require periodic verification after several years of intensive use.

From my perspective, the Ultra Q Reflex is optimized for volume and reliability, not for pushing the lowest possible energy thresholds. Clinics performing large numbers of routine procedures tend to value this balance.

Ellex (Lumibird) Tango Reflex

The Tango Reflex is positioned as a combined platform integrating Nd:YAG photodisruption with SLT functionality. While the SLT subsystem is clinically distinct, the Nd:YAG portion shares many of the same engineering constraints discussed earlier.

Publicly available specifications indicate pulse energy ranges comparable to other modern systems, with emphasis on fine energy control and coaxial optics shared between laser modalities.

Engineering observations:

- Optical integration of two laser systems increases mechanical and optical complexity because two independent beam paths must remain coaxial through the same optical train. This requires additional mirrors, dichroic elements, and tighter mechanical tolerances, each introducing potential drift points.

- Shared slit‑lamp optics demand tighter alignment tolerances to avoid cross‑calibration issues. Any small angular deviation affects both modalities, which is fundamentally different from single‑purpose Nd:YAG systems where only one beam path must be stabilized.

- Serviceability depends strongly on manufacturer support, as internal layouts are more compact than single‑modality systems. I see this as a deliberate engineering trade‑off: reduced footprint and functional consolidation at the cost of easier field servicing.

I consider combined platforms technically impressive, but inherently more complex. From an engineering standpoint, complexity is acceptable only when the clinic genuinely uses both modalities at sufficient volume.

NIDEK YC‑200 S Plus

NIDEK’s YC‑200 S Plus represents a more compact, traditionally engineered Nd:YAG platform. Manufacturer literature emphasizes stability, ergonomics, and optical precision rather than maximum output power.

While detailed internal specifications are limited in public sources, available data confirms standard Q‑switched Nd:YAG operation at 1064 nm, with fine energy adjustment and slit‑lamp integration.

Engineering observations:

- Japanese optical components are typically associated with good coating durability and long‑term alignment stability. In practical terms, this usually translates into slower degradation of focal quality over time, even if peak performance is not aggressively optimized.

- Mechanical simplicity suggests fewer failure points, but also fewer software‑assisted diagnostics. From an engineering perspective, this is a classic reliability‑versus‑transparency trade‑off: fewer things to break, but also fewer tools to detect early degradation.

Where I cannot provide deeper quantitative analysis is in internal energy feedback mechanisms; NIDEK does not publicly disclose whether closed‑loop pulse monitoring is used in this model.

Alcon PurePoint YAG

Alcon’s PurePoint YAG is positioned as a premium ophthalmic laser system, integrated into the company’s broader diagnostic and surgical ecosystem.

Publicly available materials confirm standard Nd:YAG operating parameters, but detailed engineering data—such as internal pulse monitoring architecture, flashlamp specifications, or alignment tolerances—are not fully disclosed.

Engineering observations:

- Integration with Alcon’s ecosystem suggests strong software and service support. The design philosophy here appears to prioritize system interoperability and lifecycle support over exposing internal subsystems.

- Lack of transparent technical detail limits independent engineering evaluation. As an engineer, I find this restrictive: while the platform may be robust, the inability to assess internal design choices makes it harder to judge long‑term serviceability outside authorized channels.

As an engineer, I can assess the system’s design philosophy but cannot fully characterize internal trade‑offs without access to service manuals or deeper technical disclosures.

Comparative Positioning From an Engineering Viewpoint

| Platform Type | Engineering Strength | Engineering Trade‑Off |

|---|---|---|

| High‑volume flashlamp systems | Predictable aging, simple service | Higher energy variability at low settings |

| Combined modality platforms | Functional consolidation | Increased mechanical and optical complexity |

| Compact precision systems | Mechanical simplicity | Limited diagnostic transparency |

This level of comparison is where procurement decisions become grounded in engineering reality rather than brochure language. The remaining question—how these systems behave over 5–10 years of ownership—belongs to the next stage of analysis.

Long-Term Ownership of Ophthalmic Nd:YAG Lasers: Reliability, TCO, and Real-World Risks

Once a clinic has moved past initial specifications and model comparisons, the most consequential engineering questions emerge during long-term ownership. Ophthalmic Nd:YAG lasers are capital equipment expected to remain operational for 8–15 years, often with daily use. At this stage, design philosophy, serviceability, and component economics outweigh marginal performance differences.

In my experience, this is also where procurement decisions either prove technically sound—or become a persistent operational burden.

Reliability Over Time: Which Components Fail First

When Nd:YAG systems age, they do not fail randomly. Their failure modes are strongly correlated with component physics, duty cycle, and design margins. Understanding which parts fail first, at what intervals, and at what cost is essential for realistic planning.

Flashlamps and Pump Sources

For flashlamp‑pumped systems such as Lumenis Ultra Q Reflex and similar high‑volume platforms, real‑world lamp replacement typically occurs at 5–7 million pulses in busy cataract clinics and 7–10 million pulses in moderate‑volume environments. Lamp aging manifests as:

- increasing trigger voltage (often rising by 15–25% near end of life),

- widening pulse‑to‑pulse energy variation,

- higher thermal load on the reflector housing.

From an engineering standpoint, this is a controlled degradation mode. I generally prefer this behavior because it allows clinics to schedule replacements proactively rather than react to sudden failure.

DPSS systems shift this consumable risk to laser diode arrays. While manufacturers often specify 20,000–30,000 operating hours, this assumes junction temperatures held below 30–35 °C. In installations where cooling fans degrade or dust loading increases thermal resistance, I have seen diode output decline measurably within 8,000–12,000 hours. This makes thermal design and preventive maintenance a first‑order cost factor rather than a footnote.

High‑Voltage Power Supplies and Ignition Boards

High‑voltage ignition boards typically operate at 300–800 V with peak currents exceeding 100 A. Electrolytic capacitor aging is the dominant failure mechanism, with realistic service lifetimes of 5–8 years, depending on ambient temperature.

In systems like the Ultra Q family, these boards are modular and can be replaced independently. From a TCO perspective, this is significant: replacing a single HV board is far less disruptive than replacing an integrated power module. I consistently rate modular HV design as a strong indicator of engineering maturity.

Mechanical Assemblies and Focus Offset Mechanisms

Mechanical offset mechanisms are often underestimated in TCO calculations. Systems using cam‑based or rail‑based offsets typically exhibit measurable backlash after 3–5 years of frequent adjustment. In contrast, motorized or over‑dimensioned mechanical assemblies tend to preserve repeatability longer, but at higher initial cost.

From my engineering perspective, I would rather accept a slightly larger mechanical assembly with generous tolerances than a compact design operating near its wear limits.

Total Cost of Ownership (TCO): Beyond the Purchase Price

TCO for ophthalmic Nd:YAG systems can be estimated with reasonable accuracy when component lifetimes are treated quantitatively rather than qualitatively.

Consumables and Scheduled Maintenance

| Component | Typical Interval | Practical Implication |

|---|---|---|

| Flashlamp | 5–10 million pulses | Predictable, schedulable |

| HV ignition board | 5–8 years | Temperature‑dependent aging |

| Cooling fans | 3–6 years | Often overlooked, critical |

| Illumination LEDs | 20,000–30,000 h | Low impact on TCO |

Clinics running 2,000–3,000 YAG procedures per year can expect lamp replacement every 3–4 years in flashlamp systems. This is a concrete planning figure that procurement teams should model explicitly.

Service Models and Manufacturer Support

Manufacturers differ significantly in service philosophy. Companies like Lumenis and Ellex / Lumibird have historically maintained strong U.S. service infrastructures with predictable parts availability. From an engineering operations standpoint, this reduces mean time to recovery even if parts pricing is higher.

Conversely, systems with limited regional support may offer lower upfront cost but introduce downtime risk that is difficult to quantify until a failure occurs. I generally advise clinics to ask not just “How long does this part last?” but “How long does it take to get it on site?”

Downtime Risk as an Engineering Metric

Downtime cost is rarely captured in brochures, yet it often dominates real‑world economics. A system that is unavailable for two weeks due to a proprietary board delay can cost more in lost clinical throughput than the price difference between two competing platforms.

From an engineering viewpoint, I evaluate downtime risk using three criteria:

- modularity of replaceable assemblies,

- transparency of diagnostic information,

- regional inventory of critical spares.

Systems designed with field‑replaceable submodules consistently outperform tightly integrated designs when failures inevitably occur.

Red Flags During System Selection

Based on engineering analysis rather than anecdote, I consider the following to be measurable warning signs:

- absence of pulse counters or flashlamp usage tracking,

- no published preventive maintenance intervals,

- offset mechanisms requiring partial disassembly for recalibration,

- service documentation restricted exclusively to the manufacturer.

None of these invalidate a system outright, but each increases long‑term uncertainty and operational risk.

Engineering Conclusion: Evaluating Nd:YAG as a Long‑Term Asset

From an engineering and ownership perspective, Nd:YAG platforms remain rational investments precisely because their weaknesses are well understood and quantifiable. Clinics that model pulse counts, thermal load, and service logistics rather than headline specifications are consistently better positioned over a 10‑year lifecycle.

In my assessment, the most valuable systems are not those with the highest peak energy, but those with conservative electrical design, modular serviceable assemblies, and predictable aging behavior. These qualities rarely appear on marketing slides—but they determine whether a system remains an asset or becomes a liability.

Clinics frequently underestimate TCO by focusing on acquisition cost alone. From an engineering perspective, TCO consists of predictable and semi-predictable elements.

Consumables and Scheduled Maintenance

| Component | Typical Replacement Interval | Engineering Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Flashlamp | 5–10 million pulses | Gradual degradation, predictable |

| HV ignition board | 5–8 years | Thermal aging dominant |

| Illumination LEDs | 20,000–30,000 h | Usually negligible cost |

Replacement costs vary significantly by manufacturer and service model. Proprietary consumables increase TCO but may simplify logistics. Open sourcing reduces cost but increases service complexity.

Service Contracts vs In-House Maintenance

Some manufacturers strongly encourage full-service contracts, bundling preventive maintenance and parts. Others allow trained biomedical engineers to perform most servicing.

From my perspective, systems that:

- provide clear service manuals,

- log component usage,

- expose calibration procedures,

offer clinics more control over long-term costs. Closed systems can be reliable, but they shift economic power entirely to the vendor.

Downtime Risk and Operational Impact

A technically minor failure can become operationally severe if it immobilizes the system for weeks. Factors influencing downtime include:

- local availability of parts,

- modularity of design,

- diagnostic transparency.

I generally advise clinics to evaluate not just mean time between failures, but mean time to recovery. A system that fails predictably but recovers quickly is preferable to one that fails rarely but unpredictably.

Red Flags During System Selection

Based on engineering evaluations, I consider the following warning signs:

- lack of published service or maintenance documentation,

- absence of pulse counters or component life tracking,

- excessive reliance on single-source proprietary boards,

- mechanical offset systems that cannot be recalibrated without disassembly.

None of these alone disqualify a platform, but together they significantly increase long-term risk.

Engineering Conclusion: Why Nd:YAG Remains a Rational Investment

From a purely engineering standpoint, ophthalmic Nd:YAG lasers remain one of the most rational capital investments in ophthalmology. The technology is mature, the physics are stable, and failure modes are well understood.

I do not view Nd:YAG platforms as stagnant. Incremental improvements in energy stability, diagnostics, and serviceability continue to matter more than radical redesigns. Clinics that evaluate these systems as long-term engineered assets—rather than short-term purchases—are consistently better served over the full lifecycle.

In that sense, the most important specification is not maximum pulse energy, but how gracefully the system ages.

References

- Lumenis

https://www.lumenis.com

(Manufacturer of ophthalmic Nd:YAG laser systems; reference for system architecture and service philosophy.) - Lumibird

https://www.lumibird.com

(Parent company of Ellex; reference for combined ophthalmic laser platforms and engineering integration.) - NIDEK

https://www.nidek.com

(Reference for Japanese-engineered ophthalmic Nd:YAG systems and optical design approach.) - Alcon

https://www.alcon.com

(Reference for integrated ophthalmic platforms and ecosystem-based equipment design.) - International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC)

https://www.iec.ch

(International standards for medical electrical equipment and laser safety.) - International Organization for Standardization (ISO)

https://www.iso.org

(Relevant standards for medical devices, risk management, and quality systems.) - U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

https://www.fda.gov

(Regulatory framework for ophthalmic laser systems marketed in the United States.) - SPIE

https://www.spie.org

(Technical reference for laser physics, photonics, and laser–tissue interaction.)