Central retinal artery occlusion occurs when the central retinal artery ends up being obstructed, normally due to an embolus. It causes abrupt, painless, unilateral, and generally severe vision loss. Diagnosis is by history and particular retinal findings on funduscopy. Decreasing intraocular pressure can be done within the first 24 h of occlusion to attempt to remove the embolus. If patients present within the first few hours of occlusion, some centers catheterize the carotid/ophthalmic artery and selectively inject thrombolytic drugs.

Causes of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

Retinal artery occlusion might be because of embolism or thrombosis.

Emboli may come from any of the following:

- Atherosclerotic plaques

- Endocarditis

- Fat

- Atrial myxoma

Thrombosis is a less typical cause of retinal artery occlusion but can be seen with systemic vasculitis such as SLE and giant cell arteritis, which is an important reason for arterial occlusion that needs timely diagnosis and treatment.

Occlusion can impact a branch of the retinal artery in addition to the central retinal artery.

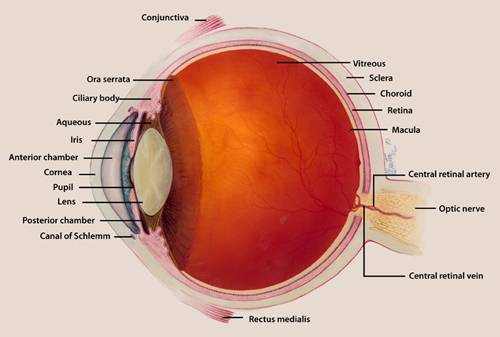

Neovascularization (abnormal brand-new vessel formation) of the retina or iris (rubeosis iridis) with secondary (neovascular) glaucoma takes place in about 20% of patients within weeks to months after occlusion. Vitreous hemorrhage may result from retinal neovascularization.

Symptoms and Signs of Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

Retinal artery occlusion causes abrupt, painless, severe vision loss or visual field problem, generally unilaterally.

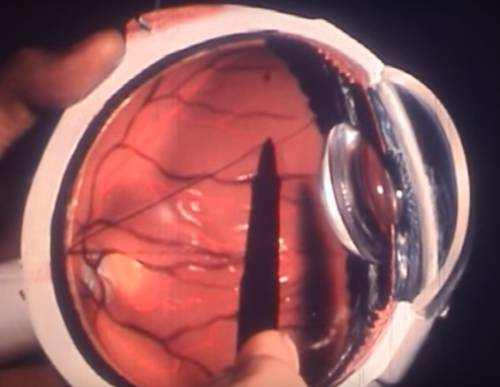

The pupil might react improperly to direct light but constricts briskly when the other eye is lit up (relative afferent pupillary flaw). In acute cases, funduscopy reveals a pale, opaque fundus with a red fovea (cherry-red spot). Usually, the arteries are attenuated and might even appear bloodless. An embolus (eg, a cholesterol embolus, called a Hollenhorst plaque) is often visible. If a major branch is occluded instead of the entire artery, fundus irregularities and vision loss are limited to that sector of the retina.

Patients who have giant cell arteritis are 55 or older and may have a headache, a tender and palpable temporal artery, jaw claudication, fatigue, or a combination.

Diagnosis

Medical evaluation

- Color fundus photography and fluorescein angiography

The diagnosis is believed when a patient has intense, pain-free, severe vision loss. Funduscopy is usually confirmatory. Fluorescein angiography is often done and reveals lack of perfusion in the impacted artery.

As soon as the medical diagnosis is made, carotid Doppler ultrasonography and echocardiography ought to be done to determine an embolic source so that more embolization can be avoided.

If giant cell arteritis is presumed, ESR, C-reactive protein, and platelet count must be done instantly. These tests may not be essential if an embolic plaque is visible in the central retinal artery.

Prognosis

Patients with a branch artery occlusion may preserve good to fair vision, but with main artery occlusion, vision loss is frequently profound, even with treatment. As soon as retinal infarction takes place (as rapidly as 90 min after the occlusion), vision loss is irreversible.

If underlying giant cell arteritis is diagnosed and dealt with promptly, the vision in the uninvolved eye can typically be safeguarded and some vision may be recuperated in the impacted eye.

Mortality/Morbidity

Patients with envisioned retinal artery emboli, whether obstruction exists, have a 56% mortality rate over 9 years, compared to 27% for an age-matched population without retinal artery emboli. Life span of patients with CRAO is 5.5 years compared with 15.4 years for an age-matched population without CRAO.

Treatment for Central Retinal Artery Occlusion

- In some cases decrease of intraocular pressure

Immediate treatment is suggested if occlusion occurred within 24 h of presentation. Decrease of intraocular pressure with ocular hypotensive drugs (eg, topical timolol 0.5%, acetazolamide 500 mg IV or po), periodic digital massage over the closed eyelid, or anterior chamber paracentesis may dislodge an embolus and permit it to enter a smaller branch of the artery, thus minimizing the area of retinal anemia. Some centers have actually tried instilling thrombolytics into the carotid artery to dissolve the obstructing embolisms. However, treatments for retinal artery occlusions hardly ever enhance visual skill. Surgical or laser-mediated embolectomy is available however not frequently done. These treatments are sometimes revealed to be reliable in little case series, however none have strong evidence to support effectiveness.

Patients with occlusion secondary to giant cell arteritis need to receive high-dose systemic corticosteroids.

Key Points

- Central or branch retinal artery occlusion can be caused by an embolus (eg, due to atherosclerosis or endocarditis), apoplexy, or giant cell arteritis.

- Painless, severe loss of vision impacts part or all of the visual field.

- Verify the diagnosis by doing funduscopy (normally showing a pale, nontransparent fundus with a red fovea and arterial attenuation).

- Do color fundus photography and fluorescein angiography and look for an embolic source by doing Doppler ultrasonography and echocardiography.

- Treat instantly if possible with ocular hypotensive drugs (eg, topical timolol or IV or oral acetazolamide), periodic digital massage over the closed eyelid, or anterior chamber paracentesis.