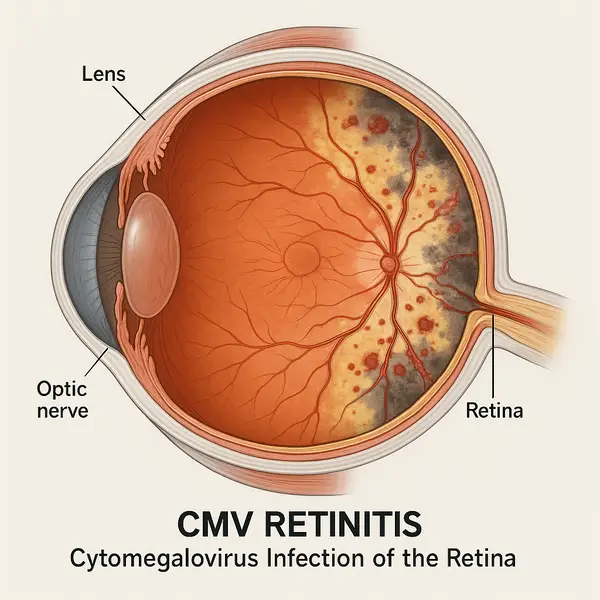

CMV retinitis is a serious viral infection of the retina caused by the cytomegalovirus (CMV), a member of the herpesvirus family. While CMV is commonly present in many people without causing symptoms, it becomes opportunistic in individuals with weakened immune systems—particularly those with advanced HIV/AIDS, cancer patients undergoing chemotherapy, and organ transplant recipients. When the immune system is compromised, CMV can reactivate and attack the retina, leading to inflammation, bleeding, and permanent vision loss if not treated promptly.

CMV Retinitis vs. Other Retinal Diseases

| Feature | CMV Retinitis | Diabetic Retinopathy | Toxoplasmosis |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cause | Cytomegalovirus (viral) | High blood sugar (vascular) | Toxoplasma gondii (parasitic) |

| Speed of Onset | Very rapid (⚠️) | Gradual | Moderate |

| Urgency of Treatment | Immediate (⚠️) | Timely | Soon |

| Vision Loss Risk | High risk | Moderate | Lower |

| Common in | Immunocompromised adults | Adults with uncontrolled diabetes | All ages, especially if exposed to raw meat or cat feces |

Source: eyexan.com

The retina, the light-sensitive layer at the back of the eye, plays a crucial role in vision. In CMV retinitis, the virus causes progressive retinal necrosis, which can destroy retinal cells rapidly if left unchecked. It’s not your everyday eye problem—this condition is a true ophthalmologic emergency.

Who’s Most at Risk?

CMV retinitis primarily affects people with CD4 counts below 50 cells/mm³, especially those living with uncontrolled HIV. Before the advent of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART), up to 40% of AIDS patients in the U.S. developed CMV retinitis. Thanks to modern treatments, that number has dropped significantly—but the risk still exists ⧉ .

Organ transplant recipients are another key risk group. Immunosuppressive medications required to prevent organ rejection make it easier for CMV to reactivate. Similarly, people undergoing chemotherapy for blood cancers (like leukemia or lymphoma) face increased vulnerability.

Who’s Most Vulnerable to CMV Retinitis?

🔴 People with HIV (CD4 < 100 cells/mm³)

At highest risk due to weakened immune defense. CMV can reactivate quickly without consistent ART.

🟠 Organ Transplant Recipients

Immunosuppressive medications reduce the body’s ability to control latent CMV infection.

🟡 Cancer Patients (esp. blood cancers)

Prolonged chemotherapy weakens the immune system and may trigger viral reactivation.

🟢 Elderly Adults (65+)

Age-related decline in immune function (immunosenescence) makes virus suppression harder.

🔵 People with Autoimmune Disorders

Biologics or corticosteroids used long-term can lower immune vigilance against CMV.

🟣 Patients with Chronic Illness (e.g. diabetes, CKD)

Chronic conditions impair systemic immunity and healing response, increasing susceptibility to CMV retinitis.

Source: eyexan.com

A recent case in Atlanta, GA, involved a 43-year-old man living with HIV who had discontinued his antiretroviral therapy. He noticed blurry vision and floaters in his right eye. Within two weeks, he experienced partial vision loss. Prompt diagnosis and treatment saved his central vision, but peripheral damage remained.

Symptoms to Watch Out For

Early detection is crucial. CMV retinitis typically begins in one eye and may spread to the other. Symptoms may sneak up gradually or appear suddenly. Here’s what to look out for—and how to interpret each sign in the context of CMV retinitis:

- Blurry vision or blind spots: This is often the first and most prominent symptom. In CMV retinitis, the virus attacks the retina, disrupting the part of the eye responsible for clear, central vision. If you notice your vision becoming blurry over days or weeks, or if you detect a persistent dark area (blind spot), especially in one eye, it’s a red flag.

- Floaters (small specks or threads in your vision): Floaters are common in many eye conditions, but in the case of CMV retinitis, they may suddenly increase or be accompanied by other symptoms. They are caused by debris in the vitreous fluid due to retinal inflammation or damage.

- Flashes of light: These can indicate retinal irritation or minor detachment—a concerning sign in CMV retinitis, as untreated infection can lead to retinal detachment. While flashes can occur in aging eyes, in immunocompromised individuals they should always be checked.

- Loss of peripheral vision: This can develop as the infection spreads across the retina. Peripheral vision loss often goes unnoticed until it becomes significant, but in CMV retinitis it’s a common progression and an indication that the disease is advancing.

- Eye pain (though often absent): Unlike other eye infections or inflammations, CMV retinitis is usually painless, which can give a false sense of security. However, if pain does occur, it may signal secondary complications like increased intraocular pressure or co-infection.

It’s important to note that no single symptom confirms CMV retinitis—but a combination of the above, especially in high-risk individuals, is cause for immediate medical evaluation. Blurry vision and floaters are typically the most consistent early indicators. Flashes and peripheral vision loss often appear as the condition worsens, while eye pain is relatively uncommon.

Because CMV retinitis can progress silently in some patients, regular eye exams are a must for those at high risk. When left untreated, the infection can destroy the retina within 4 to 6 weeks, leading to irreversible blindness ⧉

How Is It Diagnosed?

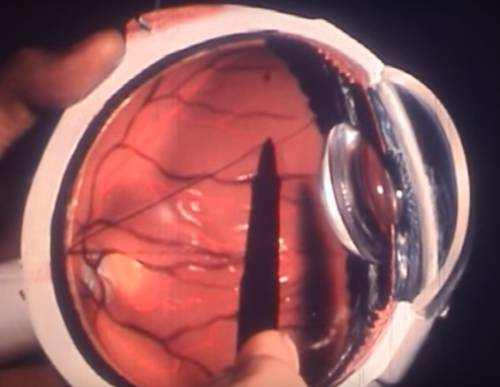

Ophthalmologists typically diagnose CMV retinitis through a dilated eye exam using an indirect ophthalmoscope. During this procedure, the doctor uses special drops to widen your pupils, then examines the back of your eye with a headset light and a handheld lens. It’s quick, painless, and takes about 10–15 minutes. What they’re looking for are characteristic yellow-white lesions with hemorrhage—often described as a “pizza pie” appearance because of the patchy red-and-white pattern.

Additional diagnostic tools include:

- Optical coherence tomography (OCT): This is like taking an ultrasound of your retina—except it uses light instead of sound. You rest your chin on a device, stare at a blinking light, and the machine scans your eye in just a few seconds. Totally painless and non-invasive. It creates high-resolution cross-sectional images of your retina to detect swelling or thinning caused by CMV. (accuracy: 8/10)

- Fluorescein angiography: This test helps map blood flow in the retina. A fluorescent dye is injected into your arm, and within seconds, a special camera takes photos of your retina as the dye moves through the blood vessels. It’s a bit more involved, and while the dye might cause a warm flush or yellowing of the skin briefly, it’s generally well tolerated. (accuracy: 7.5/10)

- PCR testing of vitreous fluid: This is the most precise method but also the most invasive. A retinal specialist collects a tiny sample of the gel-like fluid inside your eye using a fine needle. The sample is then analyzed in a lab to detect CMV DNA. The procedure is done under local anesthesia and usually takes less than 10 minutes. Some patients feel pressure, but not pain. (accuracy: 9/10)

Cost varies widely. A standard eye exam might run $100–$250 (approx. €90–€230), while specialized imaging and PCR testing can range from $500–$2,000 (€460–€1,850) depending on the facility ⧉ .

Treatment Options: What’s New?

Timely treatment is key to preserving vision. Let’s break down each treatment option in more detail so patients can understand what to expect.

Ganciclovir (Cytovene)

Ganciclovir is one of the oldest and most widely used antiviral medications for CMV retinitis. It can be administered in several ways:

- Intravenous (IV): Typically used for initial treatment in hospitals, especially for severe cases. Requires 2–3 weeks of daily infusions, then often followed by oral maintenance.

- Oral: Less effective than IV, but used for long-term management.

- Intraocular implant: A small device surgically placed in the eye, delivering medication directly to the retina over several months.

Effectiveness: Moderate to high in early stages (7.5–8.5/10).

Cost estimate: IV and implant versions can cost up to $3,000–$5,000 (€2,770–€4,620) per course.

It’s generally well tolerated but may lower white blood cell counts, requiring regular blood monitoring.

Valganciclovir (Valcyte)

Valganciclovir is a prodrug of ganciclovir with superior oral absorption. It’s commonly used for outpatient treatment and long-term suppression.

- Form: Oral tablet, taken once or twice daily depending on severity.

- Duration: Initial intensive phase (14–21 days), followed by maintenance therapy.

Effectiveness: High (8.5–9/10) when used early and consistently.

Cost estimate: $2,000–$4,000 (€1,850–€3,700) per month without discounts.

Because it is taken orally, it offers convenience, but it may still suppress bone marrow function.

Foscarnet (Foscavir)

Foscarnet is often used when the virus is resistant to ganciclovir or valganciclovir.

- Form: Administered via IV, typically in hospital settings.

- Duration: Similar to ganciclovir—2 to 3 weeks of induction, then maintenance if needed.

Effectiveness: Moderate to high in resistant cases (7.5/10).

Cost estimate: $3,500–$6,000 (€3,200–€5,550) per treatment cycle.

It requires kidney monitoring, as it can cause nephrotoxicity. Hydration before and after infusion is critical.

Cidofovir (Vistide)

Cidofovir is another second-line agent used when others fail or aren’t tolerated.

- Form: Intravenous infusion every 1–2 weeks.

- Duration: Short courses, often combined with other antivirals.

Effectiveness: Moderate (6.5–7/10).

Cost estimate: $1,500–$3,000 (€1,400–€2,800) per round.

Requires co-administration with probenecid and IV fluids to protect the kidneys.

Intravitreal Injections

These are injections delivered directly into the eye, often using ganciclovir or foscarnet. Typically used when systemic therapy isn’t enough or in combination.

- Frequency: 1–2 times per week initially, then less often as inflammation subsides.

- Setting: Performed in-office by a retinal specialist.

Effectiveness: High in localized disease (9/10).

Cost estimate: $500–$1,200 (€460–€1,100) per injection.

Many patients describe the procedure as quick and not very painful due to numbing drops.

Emerging Therapies

Researchers are exploring long-acting drug delivery systems like:

- Sustained-release intravitreal implants (e.g., investigational ganciclovir reservoirs)

- Nanoparticle-based therapies that offer targeted delivery with minimal systemic exposure

These innovations aim to reduce treatment burden and hospital visits ⧉.

Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, recommends regular viral load monitoring and CD4 count checks as part of comprehensive care. “The moment we see CD4 dropping below 100, we start preparing patients for preventive care—including retinal screening,” he advises.

CMV Retinitis Treatment Journey: Step by Step

🔴 Step 1: Initial Diagnosis & Risk Assessment

Your ophthalmologist confirms CMV retinitis using dilated eye exams and imaging tests. Blood tests (CD4 count, viral load) help determine how severely your immune system is affected. Early detection can prevent major vision loss.

🟠 Step 2: Induction Therapy (First 2–3 Weeks)

Treatment usually begins with intensive antiviral therapy to quickly control the infection. This might include intravenous ganciclovir, oral valganciclovir, or intravitreal injections, depending on severity. You may receive daily treatments during this phase.

🟡 Step 3: Maintenance Therapy

After the virus is suppressed, patients typically continue with a lower dose of oral antivirals (like valganciclovir) for weeks or months. The goal is to prevent reactivation while allowing the immune system to recover with HAART support if HIV is present.

🟢 Step 4: Immune Recovery Monitoring

During and after maintenance therapy, regular bloodwork is essential. CD4 count should rise above 100 cells/mm³ for long-term stability. Once immune strength is restored, antiviral therapy may be tapered off under supervision.

🔵 Step 5: Ongoing Eye Exams

Even after treatment, CMV retinitis can recur. Ophthalmologists recommend routine eye exams every 3–6 months for high-risk patients. Imaging may also be repeated to detect early changes in the retina before symptoms appear.

🟣 Optional: Surgical Support (If Needed)

In severe or relapsing cases, patients may benefit from sustained-release intraocular implants or even retinal detachment surgery. These options are considered when medical treatment alone isn’t enough to stabilize vision.

Source: eyexan.com

Can It Come Back?

Unfortunately, yes. CMV retinitis can relapse, especially if the immune system weakens again. Even after successful treatment, the damaged areas of the retina do not regenerate, and any new viral activity may further compromise vision. But what exactly increases the risk of recurrence—and who should stay extra alert?

What Increases the Risk of Recurrence?

The most significant factor is immune suppression. Individuals whose CD4 counts drop below 100 cells/mm³ are particularly vulnerable to reactivation. When the immune system is no longer strong enough to suppress CMV, the virus can flare up and resume its destructive path.

However, it’s not just HIV-positive individuals who are at risk:

- Organ transplant recipients: Chronic use of immunosuppressants increases long-term susceptibility.

- Cancer patients: Especially those undergoing prolonged chemotherapy for hematologic malignancies like leukemia or lymphoma.

- Elderly adults: Age-related immune decline (immunosenescence) can reduce the body’s ability to keep CMV in check.

- People with autoimmune disorders: Those taking long-term corticosteroids or biologic therapies (e.g., TNF-alpha inhibitors) may unknowingly suppress their immune systems.

- Patients with poorly controlled diabetes or chronic kidney disease: These comorbidities have been associated with higher CMV activity and slower healing.

Additionally, inconsistent adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), interrupted antiviral treatment, or lack of follow-up eye exams can all open the door for recurrence. Lifestyle factors like poor nutrition, chronic stress, or sleep deprivation—while not direct causes—can also compromise immune function over time.

Who Should Be Most Concerned?

If you fall into any of the following categories, you’re considered high-risk for recurrence:

- HIV-positive with a history of CMV retinitis

- CD4 count persistently under 100 cells/mm³

- Recently underwent an organ or stem cell transplant

- On long-term immunosuppressive therapy

- Diagnosed with an autoimmune or chronic inflammatory disease

- Over 65 with existing comorbidities

Understanding your individual risk level is critical for early detection and intervention. Regular CD4 count monitoring, ophthalmic screenings every 3–6 months, and staying compliant with treatment plans can significantly reduce the likelihood of relapse ⧉

A 56-year-old woman in Sacramento, CA, who had undergone kidney transplantation, experienced CMV retinitis six months post-op. Despite antiviral therapy, discontinuation led to relapse and partial vision loss in one eye. Her case highlights the need for long-term monitoring.

Preventive Strategies That Work

Prevention hinges on maintaining immune function. For HIV patients, this means strict adherence to HAART. For transplant and cancer patients, close monitoring by both infectious disease and ophthalmology specialists is essential.

Some high-risk patients benefit from prophylactic antiviral therapy. Valganciclovir is often used preventively in transplant centers across the U.S. Regular dilated eye exams—every 3–6 months—are recommended for individuals with low CD4 counts or a history of CMV viremia ⧉ .

Editorial Advice

CMV retinitis may be less common today than it was two decades ago, but it’s still a threat for vulnerable individuals. The good news? With better antiviral therapies, improved diagnostic tools, and vigilant monitoring, outcomes are much better than before.

Reyus Mammadli, medical consultant, emphasizes: “Never ignore changes in your vision. If you’re immunocompromised, get that eye checkup—even if everything seems fine.”

From catching subtle symptoms early to staying committed to long-term care plans, managing CMV retinitis is all about staying one step ahead. Don’t wait for the lights to go out—keep them shining bright with informed action.